Pearlette

Pearlette: A Mutual Aid Colony

Posted with permission from "The Kansas Historical Quarterly" Autumn, 1976 (copyright)

By C. Robert Haywood

Each wave of occupation of the American frontier developed its own mode of migration and settlement. For the Great Plains one of the serviceable patterns was the mutual aid or cooperative colony. Everett Dick in The Sod-House Frontier, 1854-1890, describes a number of these colonies. Many had religious affiliations such as the Mennonite settlements; others had special ethnic or life style associations, as did the black community of Nicodemus or the vegetarian colony near Humboldt.

More typical, however, was that type of cooperative colony whose constituency was drawn from a broader base within a single community or neighboring area and was motivated by an obsessive land hunger. Caught in the depressed economic conditions of the time and conditioned to think of land as man's greatest source of security, they tended to place an excessively high value on land ownership. Certainly the promotional accounts by the railroads describing the rich fertility of the soil and other aspects of nature's bounty in the West and the railroad's promise of assistance whetted the ambition of the organizers, but in truth there was little need to entice a people hemmed in by a growing population and embittered by the narrow opportunities available to them. But above all other motivations stood the hope of a better life secured firmly on land personally owned. In the words of one, ". … there was a prospect ahead: a prospect of owning a home some day. What are their prospects in Zanesville?"

The mutual aid colony was by no means a perfect colonizational system, especially the single-community-based type. Its organization was at best loose; at worst it was unplanned and chaotic. The motivation was centered on personal self-interest, an exaggerated understanding of the value of land, and an unrealistic assessment of the hazards of a malevolent nature. As a consequence, the number of failures exceeded the permanent settlements. But beyond the failure to establish a recognizable permanent community were the greater penalties extracted from those individuals who attempted the venture-penalties which Vernon Parrington described as, "The cost of it all in human happiness--the loneliness, the disappointments, the enunciations, the severing of old ties and quitting of familiar places, the appalling lack of those intangible cushions for the nerves that could not be transported on horseback or in prairie schooner."

One such colony typifying the unsuccessful effort was the Ohio or Zanesville colony which settled in Meade county, Kansas, in 1879. The original idea for the colony came from Daniel Dillon of Muskingum County, Ohio. At his cell a group organized in Zanesville, elected John Jobling as president, J. T. "Jed" Copeland as secretary, and held regularly scheduled meetings every second Saturday of the month. Eventually a constitution with bylaws was drawn up and George H. Stewart, a cashier of the First National Bank, was appointed treasurer to begin receiving funds:

Whatever its later faults, and contrary to many such projects, the colony was from the beginning a carefully and thoughtfully planned operation, at least through the talking stage. Money was raised through "donations, fairs, festivals, etc. to pay transportation charges to Kansas and buy a team for every fourth family." The developers wisely brought into the organization, for endorsement if not actual participation, some of the more prominent men of the community and called upon established service organizations such as the Odd Fellows Lodge and the local churches for support. They also displayed considerable ingenuity in devising fund raising projects; among the more unusual were the scheduling of the Hon. Schuyler Colfax for a benefit lecture and the soliciting of every farmer in Muskingum County to contribute one bushel of produce.

Through several meetings the members discussed and reported to the public possible sites, various means of transportation, prospective cash crops, and potential sources of revenue. Membership reached 60 families at one point. Eventually Howard Lowery, one of the few farmers to participate actively, was sent ahead to see at first hand what Kansas had to offer. On his return a committee of three was directed to go to Kansas "to spy out the land" and make preliminary arrangements. This advance committee chose a site in Meade County with the intention of taking adjoining claims and establishing a town as a uniting center. Since the county had not as yet been organized, the committee hoped that the county seat would be located within the limits of the 60 adjoining quarters it had selected.

On February 18, 1879, with plans complete and the timid souls separated from the bold, the party with all its possessions boarded the train that would take it as far as Dodge City. They had abandoned an earlier scheme to travel by wagon since they expected the railroad to make favorable concessions to them, and it did. Still, when the fee of $52.00 for each family was collected and all freight charges paid, "the ZANESVILLE COLONY left with $000100.00 in the hip pocket of the treasurer!"

The send-off in Zanesville was a gay one, with a large crowd at the station, tributes published in the local papers for some individuals, and expressions of the "heartiest good wishes of the community." The colony was accompanied by an agent of the railroad and was joined by another contingent from the area, which was to locate in Saline county. In spite of meager reserves, spirits were high; the euphoria of expectation overwhelmed all sense of reality.

Arriving in Dodge City on February 21, 1879, the party was met by reality at every turn. The city itself was not as wild as its reputation, but it was not peaceful Zanesville either. George Williams, one of the colonists, wrote home:

Dodge City has about one thousand inhabitants, but no very fine buildings.

The Sheriff's building, is the best, built of brick, under which is the jail, holding at present, seven Indians, the remains of Fort Robinson Massacre. The most noted are Crow, Wild Hog, Big Man. Crow is the father of Black Hawk. This place is bad enough, but it bears a harder name than it deserves. I have no doubt, but that its past history is as bad as its present name. The gold and silver region West, have taken many of the notorious characters away. We have seen no trouble yet, but have been shown many marks of kindness, by the citizens. Yet, we can hardly approve of dance houses and public gambling houses, both of which go on on Sunday, as well as any other day, but all a man has to do is to attend to his own business.

The unexpected shock was not the wickedness of "The Wickedest Town in the West," but the boom-town prices, which the Ohioans estimated were 25 or 50 percent higher than in the East. The cost of overnight accommodations for the entire colony was staggering. After a lengthy conference it was agreed that D. W. "Dunk" Arter should use $60.00 of the remaining funds to purchase lumber for a shack sufficiently large to put a roof overhead and secure the personal possessions piled along the tracks, For the adults it was a portent of things to come; for the children the whole affair was still something of a lark, a kind of exciting and extended outing. Years later one of those children, age 15 at the time, wrote of his first days in Kansas:

Here they remained a few days, all using but two stoves and occupying two beds. The beds covered the whole of each side of the shanty-- the goods piled in the center--each family in a group. About midnight of the first night, a baby in the extreme rear of the shanty took the croup. Then "there was hurrying to and fro" in hot haste to get remedies. One small boy between two grown persons remarked that he could judge of the weight of each individual accurately [sic]. They in stepping over the pedal extremities of the grown persons invariably stepped on his feet. At last the baby got better and night came to an end, as has every night since.

After several days, arrangements for the move to the "promised land" were completed. The new settlers followed the old Adobe Walls trail out of Dodge City toward "Hoodoo" Brown's Road Ranche to where their claims were. Carrie Schmoker's family was in Dodge City when the Ohio colony arrived. Since they, too, were headed for the same general section of Meade County, her family visited their new neighbors. Her recollection of the trip starting the next day from Dodge City could serve as a description of the colony's experience.

When our car was unloaded, a couple of freighters were hired, and their wagons and our own were piled high with "goods and chattels." The whole was topped by a not inconsiderable weight of human freight. We left Dodge City and crossed the Arkansas River over the old wooden toll bridge and to about three miles from the present site of Meade we saw not a single home, fence, field, or tree, nothing but the brown trail and on every side as far as the eye could reach just grassy prairie land that was not green for there had been no rain for many months. On the high flats we saw a few prairie dog towns and we met a few freight outfits going into town.

We camped that night and had our first experience of sleeping on the ground and eating food cooked over a campfire. Next morning we resumed our slow journey and some time that day we reached our homesteads where the wagons were unloaded and tents set up for our new homes.

Once settled in, the colony began its first division. Some camped near Crooked creek, going out to their claims to "prove them up"; others began the process immediately, preferring to carry water to their new homes. Addison Bennett spent his last cent in Dodge City on supplies and lumber from which he and Howard Lowery, his publishing partner, built a shanty 16 feet square and about seven high in front sloping back to about four feet. This served until a smaller but more solid sod house could be constructed. With Lowery and William Mangold, Bennett began what appeared to be a monumental task of digging a well. To their amazement water was reached at eight feet; others were less fortunate, needing to go to the depth of 50 or 60 feet.

But before the sod houses could be built, the colony's first serious tragedy struck. Both the Ed Thompson and Cyrus L. "Cibe" Atkinson families had remained in Dodge City because of the illness of children. After a few days Atkinson felt his child had recovered sufficiently to bring the family down to the claim. Bennett's reminiscences of what happened is one of the more poignant descriptions of death on the prairie:

In the morning little Pearl seemed worse, but the Atkinsons went on to their claim and left Pearl and her mother with Mrs. Bennett and Mrs. Lowery. Mrs. Mangold was also there. Pearl grew worse, and about eight or nine o'clock that morning she died. This was a sad blow. Poor Pearl! She was indeed a lovely child, aged about sixteen months, and beloved by all.

When the ladies found she was sinking rapidly, they called me and I ran rapidly down, over a half mile, and called Cibe and Sam, but she was dead before they arrived. Neighbors and friends were notified. A rude coffin was made and neatly trimmed, and on the following afternoon we laid little Pearl in the grave. I never think of that funeral procession without a tear. I can close my eyes and see it still, slowly wending its way along the point of the hill…. AlI walked, men, women and children. Four of us carried the coffin, which was covered with wild flowers. No minister of the gospel was at hand but Robert Lawson read a brief chapter from the scriptures, and reverently and sadly we laid the remains of little Pearl in her western grave.

The town, which had been named with cheerful expectation "Sunshine" in Ohio was now renamed Pearlette in memory of Pearl Atkinson, "the fairest and brightest of our jewels."

Bennett had brought with him a small press and enough equipment to set up a print shop and to publish a newspaper. This gear along with five members of his family shared the sod house. On April 15, 1879, he published the first newspaper in Meade County. The lead editorial carried a bold announcement of the colony's arrival: "Brethren of the Kansas Press, greeting!" But by then caution had touched his enthusiasm and the editorial reflected this new realism.

When we left Zanesville we thought we could get out the first issue of the Call in two weeks, but we found out different after our arrival here. We found it took more time to build our house than we had any idea of; for before we left Ohio we knew of mite meetings building four sod houses in one evening, but some-how they can't be built so fast out here; because here we build by work, and there we built by wind.

The houses and dugouts were eventually finished, and the few teams "traded around" to plow the necessary strips for "proving up" the claims. Once these essentials were underway the refinements of civilization were ordered. On April 6, the Rev. Adam Holm came out from the Methodist Episcopal church in Dodge City to hold services in Robert Lawson's home. The congregation he met was considerably sobered but still optimistic that with the Lord's blessing and a fair amount of luck their ambitions would be realized. The colony agreed to continue the religious services in the various homes.

Other evidence of permanence and stability followed. Captain Werth started a lumberyard in April and to the south R. A. Milligan established a grocery store. In May the colony members joined with others in the area in manning a militia to defend against possible Indian attacks. The adjutant general of the state, stirred by Dull Knife's raid the previous year, distributed about 50 guns and the citizens organized under the captaincy of MilIigan, who had Civil War service, with D. S. Gantz and "Hoodoo" Brown, both old timers, as lieutenants. The one and only drill held in June was strictly in keeping with American militia tradition, ending in ridiculous shambles. Later someone sent Milligan a tin sword and paper cocked hat. He never recalled the defenders.

Of far more importance to Pearlette was the designation of Bennett as postmaster of an official post office receiving delivery once a week. The area around Pearlette continued to attract settlers, although the country was still sparsely settled. In May, Bennett reported about 20 new families had located in the immediate vicinity since his last issue. Finally, as a solid symbol of permanent establishment, Ed Thompson completed the colony's first frame house.

Even with the new settlers, the region remained largely a raw, open prairie. The bleak vastness of the country was one of the unexpected conditions of their venture, which the city folk from settled Zanesville found most disturbing. The story of the first child born in the Ohio colony illustrates the point:

About one o'clock on the morning of Monday, April 7th, Dunk Arter sent Billy Bunshuh, his nearest neighbor, in great haste after Mrs. Robt. Lawson.

Billy arrived at Lawson's safely, and a moment after he started back, accompanied by Mrs. L. They had before them a walk of half a mile, due west.

An hour later they had not arrived at their journey's end, and Dunk began to get uneasy; so he built an out-fire, and started in search. Not being able to find them, Dunk started after Mrs. Billy Heinz, who lives about a mile south.

About four o’clock Mrs. Lawson and her escort, after wandering all over the township, brought up at the CALL office, about two miles south of Arter's. Here they were joined by Mrs. Bennett, and taking new bearings made another start.

All this time Mrs. Arter was alone, if we except her little children, who were all sleeping.

It was well after four o'clock when Dunk (who had also been lost) arrived with Mrs. Heinz. And there sat Mrs. Arter, holding in her arms Master Wm. Bennett Arter, a lad nearly three hours old. Mr. Bunshuh and party arrived shortly after Dunk.

Bennett's account of his own first "delivery" of the Pearlette Call is as traumatic as Mrs. Arter's issue and both illustrate the kind of optimism and willingness to gamble that mark those early pioneers. It also serves as a reminder of the sanity-saving humor essential to cope with the seemingly impossible odds the colony faced. After running off his first issue, Bennett packed his papers in a satchel and started on foot the 30-odd miles to Dodge City. At that point his major concern was the few cents cash he needed to cross the toll bridge at the Arkansas River. On the way out he sold three papers to neighbors and so had his toll, but once beyond Crooked creek valley he met no one. By midmorning the wind was so strong was forced to lean backwards against it, the heat became nearly intolerable, and his feet so blistered he was forced to remove his boots. The one respite on the trip was the chance meeting with one of the local old-timers. In Bennett's words:

Going down to Mulberry I saw a strange sight: a team coming at full speed along the trail, the driver standing up in the wagon lashing the horses. I sat down on the bluff and looked and wondered: It approached and swung up under me at a gallop. I knew at once it was Cap French, as he had been pointed out to me, although I did not know him personally. As he stopped I said to him "what are you doing down there?" He replied, "I wanted to see what dammed fool that was up there." This was our introduction and I called on him for water but he had none; I gave him a copy of the Call, and told him I must pull on. He wanted me to get in with him and return; but no, I would not turn back. Soon I said, "Well as you have nothing to drink I must go one." He promptly said, "I didn't say so; I said I had no water, and I never use it; here, try this," and he produced a three gallon demijohn. I drank it as a child would milk, and of coarse in a moment I felt it. This drink did me a wonderful sight of good, and gave me a strength that helped me up several miles. When the reaction set in I concluded that I could not possibly make Dodge, and that I would lie down and take my chances of a wagon coming along. But just then I saw ahead a large herd of cattle, as I supposed, and I knew the herders would have water. This gave me courage and hope, but alas! It was a delusion, as the cattle turned out to be the sand bluffs between five mile-hollow and Dodge. But when I got near enough to discover this the lights of Dodge flashed into view, only a mile distant apparently, and again hope was revived. But it was a long, long way, and I was three hours I suppose, making the last two miles."

All this positive activity of the colony was deceptively optimistic and was undertaken in the face of a nature, which seemed determined to thwart their best intentions. John Jobling's son remembered the summer well:

During the summer Crooked Creek went dry from its head to where Spring Creek empties into it; all the deep holes along the head of the creek cracking open like frozen ground in the winter.

The wind blew constantly and hard, a calm day was an occasion so rare that they were celebrated that first summer.

In the fall there was not more than 50 tons of hay cut between the head of Crooked Creek and where Meade now stands and all the available crop was put up.

Bennett confirmed Jobling's recollection. He recalled: "I can not now remember a shower during the year 1879 or up to July 1880 that was sufficient to lay the dust. During 1879 the prairies never got green. They did in the spring look a trifle like life, but it only lasted a few days."·

Under the circumstances the men were forced to seek day wages outside the colony. Ed Thompson and John Bay found work in a brick yard in Dodge City; William Mangold became a baker there; Dunk Arter hired out shearing sheep on the Cimarron, and "Jed" Copeland became a brakeman after being unemployed for 10 months. The dream of land ownership freeing them from other men's employ quickly withered in the Kansas sun. But there were still more troubles. As in all resettlement there was to be a physical "seasoning time." Some like Ed Thompson "came down with the ague" which they couldn't seem to shake. The long, withering summer stretched on endlessly. Fortunately, the old ties with Zanesville had not been severed and appeals for assistance were sent back "home." In June Bennett gratefully acknowledged the first box of gifts from Zanesville:

In July the first break in the solidarity of the colony came when the Howard Lowery family moved back to Kansas City' Once the ranks had been broken, the continued disintegration followed a pattern repeated in the history of many of the other mutual aid colonies. Ed Thompson's health forced him to return with his family to Ohio in August; the Muxlow family "removed to Spearville" so the children could attend school under less formidable circumstances; William Mangold's job in the bakery developed into ownership. By midwinter some of the appeals for assistance had become so desperate that railroad tickets for the Arters and Lawsons were sent from Ohio. Bennett did what he could to stem the tide of desertion, reminding his neighbors that life in Ohio had not been without its drawbacks also. In the edition marking the first year of settlement, he wrote:

During the year many of us have seen tough times, and owing to the drought our hopes may not have been fully realized: but then some of our number hoped for impossibilities.

Some of the disappointed ones have gone back to Zanesville, and it does not require much of a prophet to read their future. But some of us propose to stick to Meade County, in preference to going back to Ohio to live and die in poverty.

The disintegration was as much psychological as physical. The early exchange of kindnesses, the midnight missions of mercy on behalf of a sick neighbor, shared goods, horses, and homes turned to name calling, recriminations, and threats of violence. The long summer with its unrelenting heat, boredom, and disillusionment, eroded the concepts of brotherly cooperation and mutual aid. In Bennett's words: the people who had composed the colony, were about the most dissatisfied, troublesome and quarrelsome lot ever heard of a set of people never were before brought together who were by nature, instinct, and education so well adapted to quarrel and wrangle as the Ohio Colony . . ." "Cibe" Atkinson, the father of Pearl, whom everyone had pitied and aided at the time of her death, became in Bennett's words "a bad man in his own estimations." At one point he called on Bennett in his office and "quietly pulling out a revolver told me he had come there with the express intention of killing me." Even the individual appeals for aid resulted in controversy which spilled over into Zanesville papers hack home. G. M. Williams, who came with more reserve than the rest and with some horses from his father's livery stable in Zanesville, ridiculed the call for help and painted a glowing picture of life on the prairie. He wrote back: "I shall not disgrace Ohio's blood by accepting it." He did concede that, "If I saw some lazy thin blooded Ohioian passing by my rest, I might force him to bring me a pail of water in charity, but no more," Others felt differently and were publicly critical of "Preacher" Williams and "Our 'Worthy President" Jobling.

Efforts toward organizing a more orderly government on the basis of a municipal township only resulted in greater friction. The summer of 1879 turned into one of discord and strife. Still, hope was slow in dying. As late as May, 1879, the colony was still attracting new members from Zanesville. Mrs. L. D. Copeland, "one of the oldest citizens of Zanesville," moved with the rest of her family to Meade County, as did George Thompson. Dr. William Ward came out with the hope of settling a son-in-law and to find a spot where the Doctor "might pass his declining years." Even the bitter letter to the Courier that had sparked the taunts by Williams had ended with a half-hearted reaffirmation of the future:

I hope some day to own a good comfortable home here, and see my 160 acres under cultivation to the last foot. I read in the papers of home of how your markets are loaded with de1icious vegetables and fruit, but right here I must stop. It makes me hungry to think of peas, beans, lettuce, onions, cabbage and strawberries so plentiful there, and we have not tasted for so long. Another year at this time, perhaps I will have a different story to tell. Let me hope so, at all events.

It was a forlorn hope. The rains did not come and the few packages from Ohio did little to alleviate the situation. Bennett toughed it out through that first miserable year, but when the drought continued on through 1880 even he, Pearlette's strongest and most optimistic booster, moved on to organize the firm of Bennett and Smith, Land Attorneys, at Garden City.

Only the John Joblings and Silas Ayers of the original families remained. Born in England, Jobling had married a Zanesville girl and had eked out a living driving a "peddling wagon." Now in his mid-50's he felt he had made his last move. He had brought his wife, two sons (John Jr. and William), and his mother-in-law, Eliza J. Elwanger, who was 80 years old, on the move and they were determined to stick it out. In the winter of 1879 he had become Bennett's partner in establishing a grocery store in connection with the post office. When Bennett moved on Jobling took over the position of postmaster and added to the line of groceries. John Werth had by then sold his lumberyard and Pearlette had dwindled to one store and two houses. By October,' 1880, most of the colony had left. In 1885 Jobling reported: ".

from July 1880 to the spring of 1884, almost four years, I had but one permanent neighbor within three miles of Pearlette. "

By 1885 the worst of it was over. The settlers who had endured were seeing the benevolent side of Kansas' quixotic weather. B. F. Phillip, who lived near Pearlette, reported his wheat that year averaged 20 to 25 bushels an acre with "the heads large and well filled with a perfect grain." With improved weather conditions came the greatest land rush that section of Kansas had known. The press to file claims reached a fever pitch. The officials in the land office in Garden City reported it was necessary to enter and leave by ladder through a second story window over the heads of a constant crowd jamming the doors.

There was always a great deal of loose interpretation of the improvement necessary to establish a claim, and with the influx of new settlers there was considerable contesting of old claims and much resentment of "claim jumpers," It was only natural for the old settlers to band together to protect their holdings. On July 20, 1885, at midnight, 14 armed and mounted men visited O. S. Hurd of the Hurd & Strauss Real Estate Company in Fowler City, warning him to relinquish claims near Pearlette which he was contesting. The Fowler City Graphic was incensed by the vigilante action and charged that it was common knowledge that large bodies of land in the vicinity of Pearlette were being "held in fraud" and had "no more improvement than it had in the day of the buffalo and the wild Indian.'" Fortunately, the quarrel moved from night raids to the press with John Jobling and Oliver Norman, one of the early homesteaders, taking up the defense of the established claims. There was in fact little reason for quarrels, for there was more than enough open land in the area to satisfy the settlers. No further vigilante action was reported.

All the surrounding towns were experiencing the same quickening pace and since Meade County had been established officially and finally by the state legislature in 1885, there was much speculation as to where the new county seat would be located. Fowler City, Meade Center, Odee, Spring Lake, and Pearlette made bids for the honor. There was also much railroad talk. Pearlette's hope for transportation and survival lay with the Denver, Memphis and Atlantic railroad. Although Meade Center seemed to hold the edge for both the railroad and county seat, no one felt his town out of the race. Certainly John Jobling had high expectations, and there appeared to be some reason for his optimism. C. K. Sourbeer, from rival Spring Lake, reported: "Within the last six months four or five substantial business houses have been erected in Pearlette, the largest being that of J. Jobling. We think Pearlette will make a good town, county seat or not." In enlarging his grocery stock, Jobling was still anticipating the prosperous future he had envisioned in Zanesville. The post office continued to attract customers to the grocery store, although not as many since the Wilburn office, only a few miles to the north, was established in mid-1885 and the Fowler City and Spring Lake offices came shortly after that.

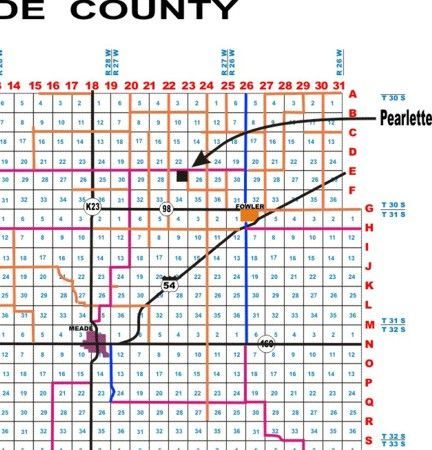

With the land rush a reality and in anticipation of the arrival of the "D M. & A," Jobling and Robert Wright filed a plat for the town of Pearlette on June 1, 1886. The town was to stand on a 1,460 feet square of the NE/4 Section 27, Township 30, Range 27.

Business for a time did pick up. T. J. Reed, who had moved in a year earlier, sold his store and hardware stock to J. Snow and the "Hotel" spruced things up a bit by planting trees on the grounds. Settlers continued to fill in the unclaimed quarters and Pearlette was enjoying a minor boom.

It was to be a short run affair. In April, 1886, after considerable complaint by Fowlerites about the erratic service, the mail to Fowler began to come directly from Dodge City, bypassing Pearlette. Then in February, 1887, two weeks after Fowler had been designated a division town by the Rock Island railroad, mail deliveries to Pearlette were discontinued altogether. Without a post office, Pearlette was not even the proverbial broad spot in the road. With the "D M & A" fading as a speculative venture and with the post office gone, Jobling finally was forced to abandon the vision he had seen in Ohio. Since settlers were pouring in, however, and since land was producing bumper crops, the choice was not to abandon the country--only the town. Jobling's alternative for continuing his store lay either with Wilburn or Fowler, or, more correctly, with the Rock Island railroad or the Chicago, Nebraska, Kansas, Southwestern railroad, both still in the talking stage. He chose the Rock Island and, as time was to prove, made a wise decision. In July, 1887, he moved his store and home the six miles to Fowler, and Pearlette was no more.

Pearlette and the Ohio colony had gone the way of many other mutual aid colonies: rising in hope, faltering on the heartbreaking reality of the prairie, and disintegrating as individuals sought their separate ways of adjusting to what life had dealt them. There were, of course, many such ventures which did succeed. Much depended on luck and timing. The Ohio colony chose the wrong summer to bid for a new opportunity. Then, too, the Zanesville settlers came with hopes too high. The story of those colonies that did succeed is one of hardship, privation, thwarted hopes, and sustained endurance. There was for nearly all a period of mean, even squalid, poverty. The price in the summer of 1879 and in the lean years immediately following did not seem reasonable to the Ohio settlers.

The Zanesville colony in many ways reaffirmed Everett Dick's contention that "the greatest weakness in the Homestead Act lay in the fact that it made homesteading too easy. The government encouraged failure by not requiring more than mere minimum .... There was no mention of personal qualification and equipment." The Ohio settlers met only the "mere minimum." Judging from the extant evidence, only Williams, who was associated with his father in a substantial business, and Arter, who was a skilled mechanic, had enough capital to support them through the normal, nonproductive seasoning time. Although the record is not always clear it would appear that only two or possibly three of the heads of family had any farming experience. Working in a "sash factory" or tending an engine did little to prepare one with the hard, practical farming sense needed to deal with the unresponsive Kansas prairie. As for equipment, the proposed team for every fourth family did not materialize, and most came without farm machinery or even a saddle horse. The long and careful planning in the end had turned out to be paper planning only. From our vantage point, it seems incredible that a man of Bennett's intelligence would bring his family to an unsettled prairie without a cent of money to sustain him until he was established, or without a team of horses to "prove up" the land he was to claim. Blind optimism seemed inordinately supported by buoyant ignorance. Yet, it must be remembered that these were young couples, most of them married less than eight years, who saw little prospect ahead of them in Ohio." Meade County represented hope--a chance for a new and better life with land, security, social position, and perhaps even fame. G. M. Williams wrote back to the people of Zanesville, half in jest, but only half:

If we had stayed in Ohio, and still been poor, our names would have died before our bodies were out of the hearse, but if we gain wealth here, grow fat with honors, ages hence mothers will be naming their babies after us, and I will prophesy that five hundred years from now half the men in the United States will be called Jed Copeland, because he was Secretary of the Ohio Colony and whipped Lawson's dog when he drew him out of his well because he was not an antelope.

The venture, however, should not be considered all failure. It did shake the members loose from the restraints that bound them to menial positions in the East. In abandoning the colony, not many returned to the old narrow opportunity. They scattered across the face of the prairie and like Bennett, Mangold, and Jobling escaped the dependency that had held them. Each became his own man in the full realization of the dream that first drove him to take the risks of coming to Kansas, that is, the full realization of owning his own land.

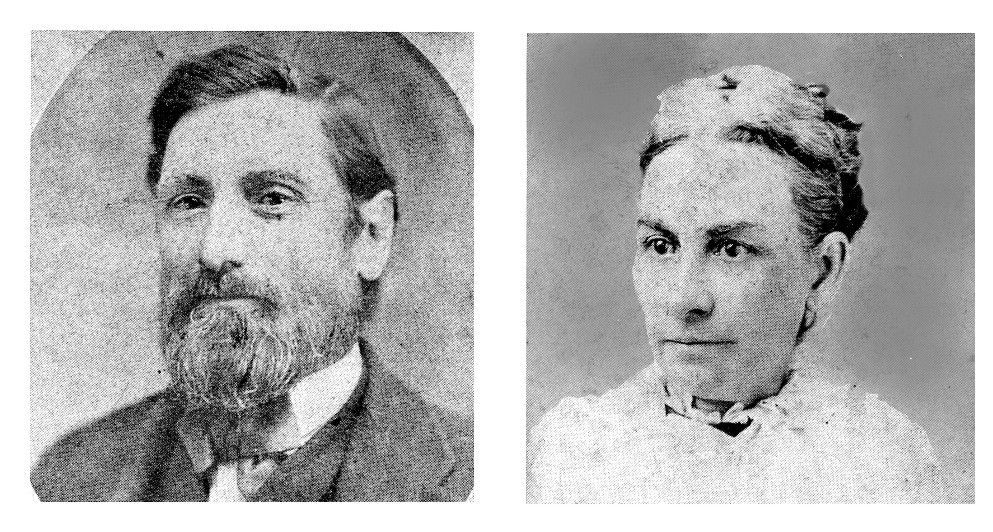

Mr. And Mrs. John Jobling of Zanesville, Ohio, who stuck it out at Pearlette until the end. Mr. Jobling was president of the Ohio or Zanesville colony that settled in Meade County, Kansas, in March of 1879. There were some 18 families from Zanesville in the Pearlette community but most had not the means and will to stay through the hard, droughty times in the years just ahead. Mr. Jobling later reported that from July, 1889, “to the spring of 1884, almost four years, I had but one permanent neighbor within three miles of Pearlette….” A railroad failed to reach Pearlette in the building flurry of the mid-1880s. In July, 1887, Jobling “moved his store and home the six miles to Fowler, and Pearlette was no more.” Photos courtesy of Casey Jobling, Wilmington, Del.

C. Robert Haywood 1921 - 2005

Bob Haywood grew up on his parents' farm in Ford County Kansas. In his lifetime he served in the U.S. Navy and enjoyed a distinguished career as a history professor and in the administration of several universities, eventually ending up at Washburn University in Topeka, KS, until his retirement in 1988.

During his academic career Haywood published nine books and over a hundred articles featured in academic periodicals. His writing style is meticulous in detail as well as entertaining, and his contribution to Kansas history is matched by few.

Haywood's book, Trails South is of particular interest to historians from Meade County as it is the definitive history of the Jones and Plummer Trail that ran from one end of the county to the other in the mid to late 1880s.

VISIT OLD MEADE COUNTY

CONTACT US

Museum:

620.873.2359

info@visitoldmeadecounty.com

200 E.Carthage, Meade, KS

Dalton Gang Hideout:

620.873.2731

daltonhideout@yahoo.com

502 S Pearlette St, Meade, KS