The Cheney Family

SETH & SARH (BEST) CHENEY

In the second half of the year 1882, Seth Cheney made the two-hundred mile trip from the Texas panhandle to Meade County in southwestern Kansas, most likely following the Jones and Plummer Trail. With this move, his journey was complete. His reasons for making this move at age 50 are not fully known, but we are fairly certain the earlier relocation of the Best family was a strong inducement. Sarah Matilda Best, the pretty young daughter of William and Matilda Best, had caught Seth’s eye when they were all in Donley County, Texas near Old Clarendon. The Bests moved to Meade County sometime in 1881, ending their own long migration from Pennsylvania, and Seth seems to have followed them, his heart conquered by a girl about thirty years his junior. Despite this difference, described by Seth as “a broad chasm,” they were joined in marriage on 6 Sept 1882 in Dodge City, Kansas. Meade County had not yet been organized for governmental purposes, and Dodge was the closest place for someone to “get hitched.” Although there is no clear evidence, we believe Seth was not a stranger to his new home. As a stockowner in Texas, he had sold both sheep and wool in Dodge City. Sometimes he used an overland freight hauler. We suspect atother times he made the trip himself. His route to Dodge likely would have been through Meade County, for the Jones and Plummer Trail dissected the county. He saw land suitable for ranching. The territory was still mostly unsettled, having been passed over for years as part of the “Great American Desert.” Not until about 1885 would a rush of settlers come to these parts, so Seth Cheney and the Bests virtually had their pick of the land. Seth Boynton Cheney was born 20 October 1832 in Waterville, Franklin County (later part of Lamoille County), Vermont, the oldest child of Samuel Boynton and Lucy Barrett (Wright) Cheney. Samuel was born in New Hampshire, but raised in Vermont from the age of three. He was from the Cheney line that traces back to John Cheney of Newbury, Massachusetts, and previously from Mistley and Lawford parishes in Essex County, England. Lucy, born in Bakersfield, Franklin County, Vermont, was descended from John and Priscilla (Byfield) Wright of Woburn, Massachusetts. Seth’s father was a well-respected man in Waterville, being elected to municipal offices, serving as school district treasurer, and being called to jury duty. He owned fifty acres of land in Waterville, upland acreage on the town’s north side, more suited to pasturage and sugar maple harvesting than to crops. School records for individual students in this era do not exist, but we can be sure, because of his dad’s interest and involvement in education, that Seth attended school. It is likely that Seth received a well-rounded education that included book learning of the three “Rs,” as well as practical skills required to work marginal land. The farmer in upstate Vermont had a hard job of making the land produce a living sufficient to support a family. Maple syrup was definitely a cash crop. Looking back on how they did this in the 1830s-1850s, it was a labor intensive production, using specialized tools, with a small season to work with. A few weeks from late February till about the first of April was all you had to gather the sap and render it into syrup. We don’t know for sure that, while in Waterville, Samuel Cheney harvested maple sap and rendered it into maple syrup. We can reasonably assume that did, however, as he owned woodlands and since this was prime maple syrup territory. Once Samuel moved to Lowell, however, our certainty goes even higher. Half of his land was in what was described as a wild lot. Fifty acres of trees: some to burn, some to harvest for miscellaneous woodworking needs, but most to keep and tend for maple sap gathering. The fact that “sugar tools” were part of Samuel’s estate is a good indication that sugaring was part of the Cheney farm regimen. Samuel sold his Waterville land in 1846, and moved the family to Lowell, twenty miles east. Seth was thirteen at the time, one of four siblings still living. The general landforms there, in Orleans County, were not quite as mountainous as in Lamoille County, but the land was not much more hospitable. The reasons for Samuel’s move are not clear. His land holdings were somewhat larger in Lowell, so perhaps cheaper land was the inducement. The life of a boy on a farm in northern Vermont acquainted Seth with much hard work. These farms tended to be 50 to 100 acres, normally on hillsides—how fortunate were those few who had their land in the narrow river valley!—and mixed between a variety of farm animals and small crop plots. It seems the only cash crop was maple sap harvesting and refined maple sugar products. No doubt Seth learned this trade, as well as the rudiments of truck farming and animal husbandry. He learned to care for the farmer’s tools, and the structures of the farm: fencing, buildings, even simple roads. He learned to deal with several feet of snow in winter, and the relatively short summer growing seasons, always with abundance of water. By the time 1849 arrived, the year Seth would turn seventeen, he probably knew enough to run a farm on his own. But then, it was not farming that caught his fancy. Nor was the promise of participating in democracy in action for years ahead sufficient to restrain him from seeking that which allured many at that time and for many decades of our history: gold. We assume, based on family stories, that Seth left for the Gold Rush in 1849 at age 16, and made it at least as far as San Francisco. His obituary says he spent four years in the gold fields. Did he? Or did he find conditions in either San Francisco or Sacramento so difficult that going on to Sutter’s Mill was too difficult? We assume that Seth had a decision to make. Go home (assuming he had the money for the trip), or find a place to live, settle down, possibly find a wife and raise a family. From what we have been able to determine, he did the latter—in Northern California. From current research we have found no footprints left by Seth in California during the Gold Rush years. That’s not to say he didn’t go, but we find no written record that he did. Sometime between 1850 and 1860, Seth arrived in Humboldt County in Northern California. This was a part of California that was populated by the overflow of men from the main gold rush areas further south. Into this county came Seth, using his middle name, Boynton. If he had come to the gold fields in 1850, he likely did not make his fortune; indeed, we don’t even know if he had the funds to go the last leg of the trip from San Francisco to the gold diggings. Either way, hunting for gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills didn’t pan out for Seth, and he sought another place to make his fortune. Northern California was a good place. Miners from the Sutter’s Mill area had gradually worked their way north, into the Sacramento Valley and what is now Trinity County. Places such as Weaverville and Big Bar were only fifty miles from the coast; yet, several years elapsed before the miners made the difficult trip over the coastal ranges into what became Humboldt County. How did Seth get there? Did he work his way up to the northern diggings, then cross the rugged coastal ranges on foot or horseback? Did he go by boat from San Francisco, landing in the beautiful anchorage afforded by Humboldt Bay? It appears that Seth Cheney was involved in agriculture during his time in Humboldt County. That is not to say whether he went there for mining or not. But the wealth in Humboldt County lay not in gold, but in other resources: the towering redwood trees; the excellent harbor of Humboldt Bay; its strategic location on the Pacific coast; the hardiness of the original settlers. Seth Cheney came to California to find gold and make his fortune. He may never have found the dust and nuggets he craved, but he seems to have done alright by himself. Having arrived at a newly developing area fairly early, he was able to acquire property cheaply and sell it later at a profit. He did business with some of the leading citizens of Humboldt County. He may have been involved in a large ranching operation, selling out his share for a sizable profit. It was said that Seth came to Meade County, Kansas in 1882 with $10,000. It seems he accumulated some of this—perhaps most of it—in Humboldt County. Sometime between 1875 and 1879, Boynton Cheney disappeared from the Humboldt County records. Why did he leave the beauty of Northern California for the stark Texas panhandle? We may never know the answer to that question. Did he and Emily, his common law wife in California, have problems? Did he have restless feet that fifteen to twenty years in one place had failed to cure? Whatever the reason, Seth turned his back to the Pacific, with the beauty of the redwoods, the ocean, and the mountains, and headed to the Great American Desert. Donley County, Texas, directly east of the City of Amarillo, is a bleak place. Flat, dry, windblown, hot in summer and cold in winter, it seems an exact opposite of Humboldt County, California. The main geographical feature of Donley County, apart from the plain, is the beautiful Palo Duro Canyon. The plain is broken in a few places by low, rolling hills. Seth arrived in Donley County sometime between 1875 and 1880. Given that he had a sizable herd of sheep by 1881, it seems he must have been there at least a few years before that. The 1880 census finds him living alone, age 50, his birthplace Vermont, his occupation a stockman. Adjacent families were a mix of Hispanic and Anglo names. Most of the listed occupations were related to ranching. No specific address is given for Seth, just the town of Clarendon. The trek west was different for William James Best and his family. Their story begins in Pennsylvania, in Lycoming County in the north-central part of the state. It is there in Williamsport that William married Matilda Hively on May 8, 1851. William was about 26, and Matilda about 30. Shortly after their marriage, the Bests made the trip west to join William’s father and his siblings in northern Indiana. They resided for a short while in Harris Township of St. Joseph County, where their oldest child, John Hively Best was born. About 1853 they moved across the state line to neighboring Cass County, Michigan, and settled in or near Dowagiac in Wayne Township. This move was only 15 to 20 miles, and other members of the family were already in Cass County. The Best’s other children were born in Cass County: James Nelson on Feb 26, 1854; Mary Ellen on August 6, 1857, and Sarah Matilda on July 4, 1860. The Bests did not find what they were looking for in Michigan. Sometime between 1860 and 1870 they moved again, this time over five hundred miles south and west to central Missouri, to the town of Utica in Livingston County. These were sad years for the Bests. Two of their four children died in Livingston County. The Bests were likely in Utica for less than ten years before they moved on, six hundred miles further south and west, to the Texas Panhandle. Sometime after 1871 and before 1880, the Bests arrived in Donley County, their next to last stop. Neither the Bests nor Seth Cheney were in Donley County very long. I estimate that both of them came sometime around 1876 to 1878. They were gone by 1882, moved on to Meade County, Kansas. We know that Seth put together a herd of sheep. We don’t know, at this time, if William Best farmed, or lived in Clarendon and worked at a trade. In this short time, and with no organized county government, the paper trail is rather thin. Only the 1880 census report, a tax record, and a couple of newspaper shorts tell us what our family did in Donley County. The rest we know only from family lore. During this time both Seth Cheney and the Bests became acquainted with Donley County’s most famous citizen, Charles Goodnight. Col. Goodnight was putting together a cattle herd on what became known as the JA Ranch, in that part of Donley County that is close to the Palo Duro Canyon. Goodnight’s ranch stretched into neighboring counties to the south and west. How he and Seth made acquaintance is not known. The records show that both Seth Cheney and Charles Goodnight were members of a grand jury convened in Mobeetie in December, 1881. Family lore says that Seth and Charles were friends, that possibly they “rode together.” Charles Goodnight ran cattle, while Seth Cheney herded sheep. Normally the cattlemen and the shepherds did not get along, but Seth and Charles seemed to. Tradition has it that some of the Goodnight cowboys made plans to drive the shepherds away, kill them if they had to, but Charles put a stop to it. Family lore says that, years later, Sarah Matilda wrote to Charles Goodnight, who was in his nineties at the time. She received a reply from him, saying that he remembered her family. It was in Donley County that the Bests added the last member of their family. She was not a natural child, for Matilda was 58 years old when the Bests arrived there. No, it was an adopted daughter, Jessie. She was the daughter of Dora Allian, who couldn’t care for her. The Bests accepted baby Jessie into the family, and she became known as Jessie Best. In Jessie’s biography, written by one of her daughters, Sarah Matilda is described as Jessie’s foster sister, and Nelson Best as her foster brother. Just as Pennsylvania, Indiana, Michigan, and Missouri did not provide what the Bests were looking for, neither did the Texas Panhandle. They had one more move to make, this time two hundred miles to the north, to Meade County in southwestern Kansas. Tradition, confirmed by the circumstances described in the letter from Seth to Sarah, has it that the Bests moved first, in 1881, and that Seth followed in 1882. The Bests and the Cheneys settled in what became Logan Township, about eight miles south of where the town of Fowler would be established. Since there was no government at the time, Seth and Sarah went to Dodge City to be married on September 6, 1882. They immediately began the process of establishing a cattle ranch. Family lore says that Seth had money when he came to Meade—$10,000. This made him one of the wealthiest men in the county. While he at first built a dugout home into a hillside to live in, the Cheneys were one of the first rural families in the county to have a board home. By the time the rush of settlers came in 1884-1885, the Cheneys and the Bests were already established on their land. Nelson Best ran the land for his aging parents. We don’t know if they were involved with livestock or with crops. Seth and Sarah appear to have immediately gone into ranching. Their children began arriving soon after they settled in Logan Township. William Boyton Cheney was born July 31, 1883. He was followed by Clarence Lee Cheney on July 11, 1885, and James Herman Cheney on July 30, 1888. So their first three children were boys. Why did they move to Meade County? Why not stay in Texas? The two places were not that much different. Both are semi-arid plains with hills and valleys punctuating an otherwise flat landscape. Recent information has come to light that Sarah Matilda may have had relatives in the area. A clipping in the Dodge City Globe, date of issue unknown, included a regular feature of historical notes from newspapers from years before. In one of these columns, the following news report from prior years was quoted: “Miss Eva Williams, of Missouri, who has been visiting her cousin on Crooked Creek, miss Matilda Best, for a few days, is now visiting Dodge City, the guest of her aunt, Mrs. W.W. Robbins.” So, Sarah Matilda may have had an aunt in Dodge City! I have not yet done any research into who Eva Williams might be, and whether Mrs. Robbins was a relative only of Eva or also of Sarah. The original news items must have been from the years 1880 to 1882, before Sarah and Seth married. Seth was known throughout Meade County as a kind man, quiet and gentle in nature, and generous to a fault. He had a blacksmith’s shop at the ranch, and never hesitated to fire it up and make repairs when neighbors came by with a need, always refusing to accept any kind of payment for his time, know-how, or equipment. It is said he was an excellent father, always willing to gather the little ones around him and tell them stories of the gold rush and the “old” west, or about the sun and the stars. Some of these stories, though not many compared to all he must have told, have been passed down by Seth’s children to younger generations. It is notable that Seth Cheney was never elected to any county offices. He appears to have kept to himself, tending to his ranch and his family. He was 56 years old in 1888 when we find his name on a deed in Meade County, selling land to the County. I’m not sure how he acquired that land. Over the next twelve years, Seth’s name often appears on deeds, and most often on tax deeds. Through purchases from the county for back taxes on land abandoned by departed settlers, the Cheneys were able to expand their land holdings to about 2,060 acres, all in Logan Township. This is not a huge ranch, either by today’s standards or for that time, but it was sufficient for the family’s needs. The Cheney ranch was not a contiguous parcel of land. It included several quarter-sections of land, some of which were connected, some which weren’t, but all of which were in Logan Township. The place on which the house and ranch buildings were built was on a small branch of Crooked Creek. Seth lived on this land for about twenty-five years. Seth’s and Sarah’s family continued to grow. Their first daughter, Cora Ellen Cheney was born October 18, 1890; Walter Howard Cheney, their fourth son, on May 31, 1894. Another daughter, Rose Mary Cheney, joined the family on March 19, 1896. The family was completed on January 23, 1899, when Charles Robert Cheney was born. Seth was 66 years old by then, and Sarah about 39. A recollection, passed down through the Charley Cheney family, concerns the blizzard of 1886. Here is how Wayne Boyton Cheney described it in 1981: My mother, Elva Cheney, recalls the story of another blizzard, here at Fowler, Kansas, in the year 1886, told to her by our dad, C.R. Cheney. This would have been long before dad and most of his brothers and sisters were born. Grandfather [Seth] had built a house in some canyons by a sandy stream a few miles south of Fowler, (the original house is still standing). He had brought a wagon load of lumber from Dodge, intending to add on to the small house as his family was growing. But the blizzard was so bad that there was no way they could get out to cut additional firewood, so the lumber was burned to keep the family alive thru the intense cold. When Seth’s grandson Darrell LeFever said the Cheneys “were the only ones in that part of the country with anything,” we wonder what “things” they might have had. The house was plain and small, and their 2060 acre farm was not overly large by the standards of the day. The blacksmith’s shop was clearly something extra that they had which others didn’t. The early photo of the ranch shows fencing and outbuildings and perhaps a barn and a storage building. In correspondence it is mentioned that they had a threshing machine. Then there is the famous clock, a mantle clock, which Seth purchased for Sarah from the Montgomery Ward’s catalogue for their first anniversary. This was no doubt a luxury that most families couldn’t afford. Sarah kept that clock into her old age, when she had moved off the ranch and into Fowler. A story told in the Clarence Cheney family is that a picture of Sarah and this clock was on the cover of the Montgomery Ward catalogue one year. Seth Cheney turned 74 years old on October 20, 1906. At that time he had five children still in the home: James Herman, 18; Cora, 16; Walter, 12; Rose, 10; and Charley, 7. Seth had the ranch, and by all accounts some money in the bank. The ranch was one of the best in the county, with who knows what other improvements. He had become successful at what he did, and had a lifetime of memories, only some of which he had passed on to his children. It was the following spring when Seth Cheney came face to face with his Maker. Typical for him, he could not go out by any normal means. In April he was on a horse, on the ranch, and while we don’t know exactly what he was doing, and without getting too graphical, he had an accident, in which his testicles were injured, perhaps crushed in a saddle. This resulted in an illness of several days, from which he never recovered. He died on April 18, 1907. His death certificate lists the cause as “Strangulatia Hernia”. He was laid to rest in Fowler Cemetery, eight miles north of the ranch, not far from his in-laws, William and Matilda Best, who died in 1901. His obituary called him “one of Meade County’s oldest and most respected citizens”. Newspaper accounts state that the funeral was held over until a couple of his sons could make the trip from Colorado or New Mexico. Probate activities began a week after his death, though the ranch was not sold off until 1916. Sarah Matilda (Best) Cheney lived 36 years as a widow, until 1943. By 1920, she was living in Fowler, with 21 year old Charley the only child left at home. Most of Sarah’s remaining years were spent in Fowler, though she traveled to visit her children: Clarence in Wichita, Cora in Wichita and then southern Texas in the Rio Grande valley, and Herman and Walter in the Phoenix area. She was visiting in Phoenix when Herman died of influenza at the age of 46. Will Cheney died in 1916, murdered in a property dispute, perhaps regarding where a fence was constructed. Charley, the youngest, was her only child to remain in Fowler. Her house in Fowler was on Elm Street. Charley lived nearby, and as did her adopted sister Jessie (Best) Hill, each with their children. Sarah lived to see all her grandchildren born, and all outlived her. So Sarah Matilda’s life came to an end. She was laid to rest in Fowler Cemetery next to Seth, with the remains of her brother, father, mother, and two sons, and grandchildren close at hand, the end of a long, long journey for her. Recent research has proven that Seth was in Massachusetts in 1855, which raises the question: Did he really go west in the Gold Rush? Maybe he did and then went back East before arriving in Northern California, or maybe he never actually went West for gold. So maybe Seth exaggerated a bit on his “resume.” He said he was a 49er, although we have no proof of it and have good reason to believe it really wasn’t true. Did Sarah know? Did she know Seth had had a wife and child back in Massachusetts when he was supposedly hunting for gold in California? Did she know he had a common law wife in California, and a stepson? Or did she just pass along her husband’s stories as she remembered them after his death? Everyone today seems concerned about their legacy. How will people think of me after I’m gone? Will I have left them in a better situation than they would have had without me? How will history judge me? What is Seth Cheney’s legacy? And Sarah’s? Seth’s descendants tend to think of him as a romantic figure—the gold seeker, the cowboy, the man who married a sweet young thing in his later years. Sarah we also see as a romantic figure. Dragged from place to place by parents who had troubling fining their place in the world. She married an adventurer much older than her. After his death, leaving her a 47 year old widow, she didn’t have an easy life, and saw her share of additional sorrow. But what should we think of them? Both joined hundreds of thousands of others in the westward expansion of this country. Seth made a big jump on his own, and lost contact with his family in New England. Sarah made smaller moves with family, sometimes to join other family, and for a while they kept in touch with relatives in Pennsylvania. Their story is similar to many who made the trek west. Their story is, in a way, the story of America in the 1800s. Seth certainly lived a life that, in hindsight, looks colorful and adventurous. Whether he sailed around the Cape, or crossed the Isthmus, or made his way overland, he had an adventure getting to the gold fields—if he went at all. Whether he never made it during the Gold Rush or not, he still went to California. After that, however, Seth lived a life that appears to have been quiet. He worked for his keep. He rented or bought land. He married. He joined a militia to fight Indians. He registered to vote. He homesteaded and became a rancher. Then the mystery came again. He sold his land, parted from his second wife, and moved on. He started another ranch. He married again and had a family. He started yet another ranch. He died as a result of a freak accident. He told his family little or nothing of his earlier life in California. Most of this is mundane, except for the places, distances, and dates involved. If Seth had told his second family about his first, or his third about the first two, if he had fully accounted for the thirty missing years in the stories he told, we might look upon him as a little less of a romantic figure. We hope he didn’t abandon his first and second wives and leave them wondering what happened to him. We hope each marriage ended before the next began. We hope he moved from place to place for legitimate reasons, not because he was running from the law. Perhaps we think a little less of Seth because he hid much of his past from his descendants. Despite these latest finds of Seth’s unexpected footprints, we still see him as a romantic figure. His descendants should take time to know him, as best they can; to study the times he lived in; and the places; and to draw from his life the good things about our nation, and the pioneers who moved across it and built it. So, Seth and Sarah Cheney’s story is closer to being told, and their legacy grows.

The Cheney Family around 1898

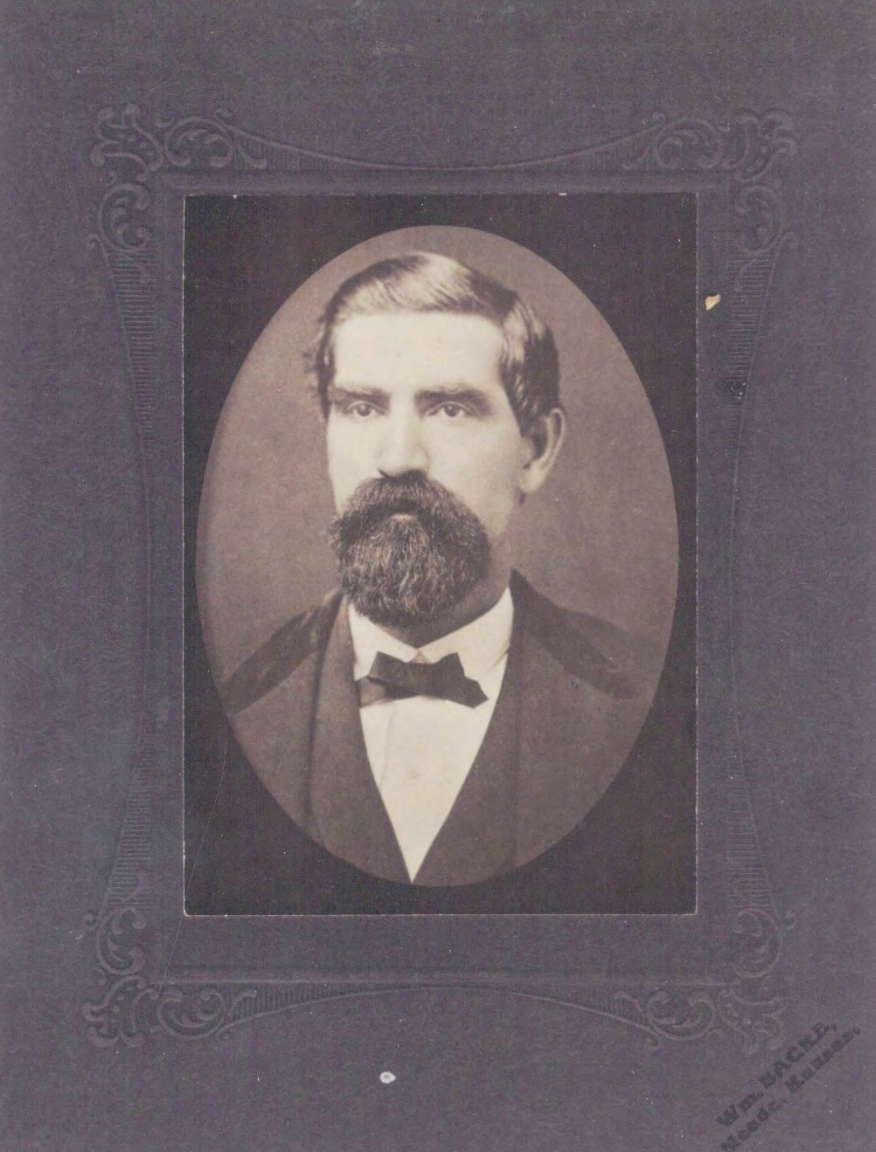

Seth Cheney